More than 40 years after the end of the Khmer Rouge regime, Cambodia still lives with the ghosts of war buried beneath its soil. An estimated 4 to 6 million landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO) remain scattered across the country - enough to cover nearly 2,000 square kilometers. These aren’t relics from a distant past. They’re active, deadly, and still maiming and killing people today.

Why Cambodia Has the World’s Worst Landmine Problem

Cambodia’s landmine crisis didn’t start with one war. It built up over decades. During the Vietnam War, bombs rained down on border areas. Then came the Cambodian Civil War, followed by the Khmer Rouge’s brutal rule from 1975 to 1979. The regime planted mines to control territory, punish dissenters, and defend remote villages. After the fall of the Khmer Rouge, fighting continued between government forces and rebel groups well into the 1990s. Every side laid mines - anti-personnel, anti-tank, cluster munitions - often without maps or records.Today, the most heavily contaminated areas are in the northwest: Banteay Meanchey, Oddar Meanchey, and Siem Reap provinces. These are rural regions where families farm, children play, and elders walk to market. There’s no warning. No fence. Just dirt, grass, and a hidden death waiting to trigger.

The Human Cost: Amputees, Children, and Lost Livelihoods

The numbers are staggering. Over 40,000 Cambodians have lost limbs to landmines since the 1970s - one of the highest per capita rates in the world. In 2024 alone, 49 people were killed or injured by mines or unexploded bombs. About one-third of those killed or injured are children. Most are boys, often playing near fields or rivers where mines have shifted with the rain.Survivors don’t just lose a leg or an arm. They lose their ability to work, to go to school, to move freely. Many live in remote villages, hours away from hospitals. The International Committee of the Red Cross found that only 25% of mine victims reach medical care within six hours. For 15%, it takes more than three days.

And it’s not just physical. A farmer in Siem Reap told an aid worker in 2024 that he used to grow rice on two hectares of land. After his field was cleared in 2023, his harvest tripled. That’s the other side of the coin: land that can’t be used means poverty that can’t be escaped. Eighty percent of mine victims come from rural communities - places already struggling to feed themselves.

How They’re Clearing the Mines: From Metal Detectors to HeroRATs

Clearing mines in Cambodia is slow, dangerous, and expensive. For years, teams of deminers walked slowly through fields, waving metal detectors over the ground. One person might clear 20 square meters a day. In the rainy season, that drops by 60%.Then came a game-changer: mine detection rats. APOPO, a Belgian NGO, started training African giant pouched rats - called HeroRATs - in 2015. These rats weigh less than a kilogram. They can’t trigger a mine. And they smell TNT. One rat can scan an area the size of a tennis court in 20 minutes. A human team would take days.

By 2025, APOPO’s rats had helped clear over 2,600 anti-personnel mines and nearly 2,500 other explosive items across Cambodia. They’ve returned land to farmers, schools, and roads. One village in Banteay Meanchey now grows cassava on land that was once marked as “highly contaminated.”

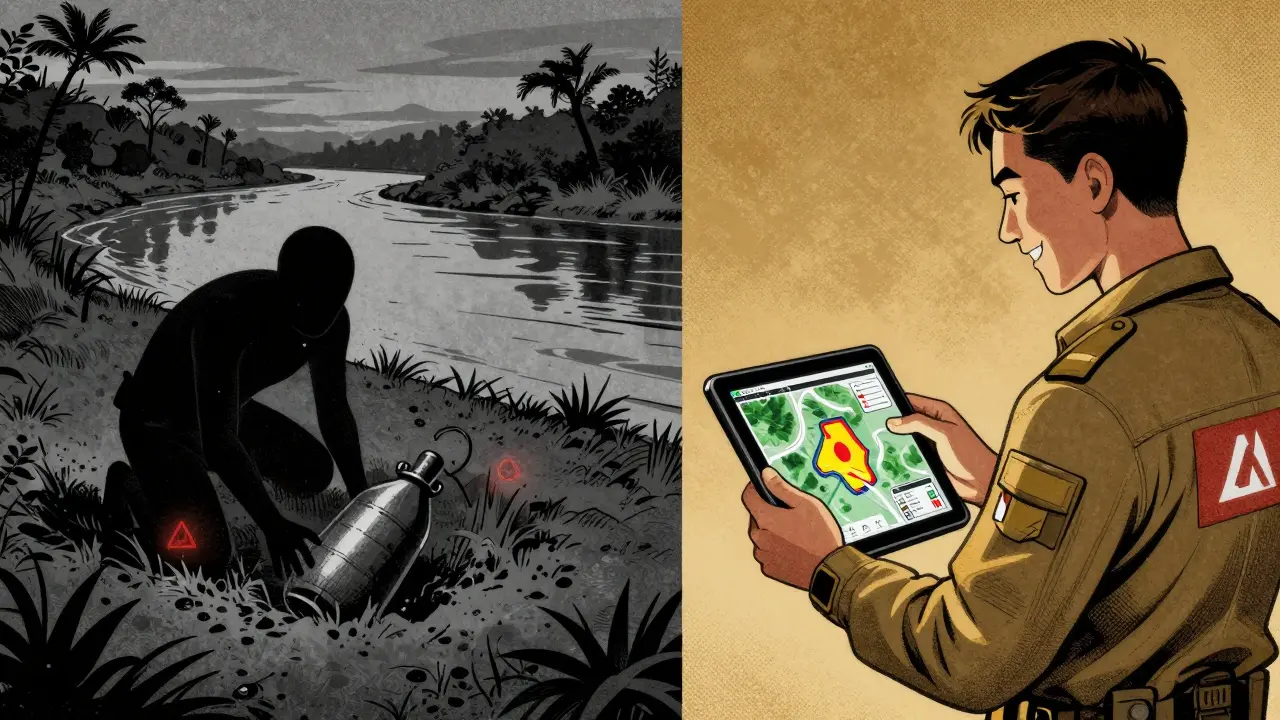

The New Frontier: AI Predicting Where Mines Are

The next leap came in 2025, when NEC Corporation and the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC) unveiled an AI system trained on decades of data: where mines were found, where fighting happened, where people reported suspicious spots, even satellite images of terrain changes.The system doesn’t find mines. It predicts where they’re most likely to be. In a test covering 1 million square meters, it matched actual mine locations with over 90% accuracy. That means deminers no longer have to scan every inch of a 10-hectare field. They can focus on the 20% most likely to be contaminated.

This cuts survey time by up to 40%. It saves money. It saves lives. And it’s already being used across five provinces. Villagers now report suspicious spots via a mobile app - and that data feeds back into the AI. It’s not magic. It’s smart, data-driven work.

The Money Problem: Who Pays to Clear the Mines?

Clearing mines costs money. A lot of it. Experts estimate Cambodia needs $40 million a year just to keep up. In 2024, it received about $35 million from donors: Japan gave $12 million, Australia $8 million, the United States $7 million. The rest comes from Cambodia’s own budget - a stretch for a country still rebuilding.But global priorities are shifting. Wars in Ukraine and Gaza have drained humanitarian funding. Donors are tired. Some experts warn that Cambodia could lose 20-30% of its funding by 2027. If that happens, clearance could stall. The 2030 target - already pushed back from 2025 - might slip again.

The Dark Shadow: New Mines Laid Along the Thai Border?

There’s a terrifying twist. In 2025, Thailand presented evidence to the United Nations that Cambodia had laid new landmines along their shared border. Thai soldiers were injured. The mines were modern, not old leftovers.Cambodia denies it. But the evidence is real. This is a violation of the Ottawa Treaty - the international agreement Cambodia signed in 2000 to ban landmines forever. If true, it undermines decades of trust, hard work, and global support. It also means the problem isn’t just historical. It’s still growing.

What’s Next? The Road to 2030

Cambodia cleared 273 square kilometers of land in 2024 - the most in a single year ever. That’s progress. But there are still over 1,900 square kilometers left. At the current pace, the country will need more than five years just to catch up.The government says it’s on track for 2030. But that depends on three things: funding, technology, and honesty. If funding drops, even the best AI won’t help. If new mines are being laid, then clearance becomes a losing game. And if the world stops paying attention, Cambodia will be left alone with its buried past.

What’s clear is this: the people clearing these mines aren’t soldiers. They’re farmers, teachers, and former soldiers who lost limbs themselves. One CMAC technician said, “I clear 100 square meters a day. I think about the child who might play here next year. That’s what keeps me going.”

The land is healing. Slowly. But the scars run deep.

How many landmines are still in Cambodia?

Estimates vary, but the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC) says between 4 and 6 million landmines and unexploded ordnance remain buried. Some independent sources suggest the number could be as high as 10 million. These devices are spread across roughly 1,900 square kilometers of land, mostly in rural areas near the Thai border.

How many people have been killed or injured by landmines in Cambodia?

Over 40,000 Cambodians have lost limbs since the 1970s due to landmines and unexploded ordnance. In 2024, there were 49 recorded casualties - 22 deaths and 27 injuries. Children make up about one-third of victims, mostly boys playing near fields or rivers where mines have moved due to rain or erosion.

Who is clearing the landmines in Cambodia?

Clearance is led by the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC), a national agency, alongside international NGOs like APOPO, HALO Trust, and Mines Advisory Group (MAG). More than 2,000 Cambodian deminers work across the country. APOPO’s mine-detection rats and NEC’s AI prediction system are now key tools in the effort.

Are landmines still being laid in Cambodia?

Cambodia officially banned landmines in 2000 under the Ottawa Treaty. But in 2025, Thailand presented evidence to the UN that new mines had been laid along the Thai-Cambodian border, injuring Thai soldiers. Cambodia denies this, but if true, it would be a serious violation of international law and could derail decades of progress.

How long will it take to clear all the landmines in Cambodia?

Cambodia’s official target is 2030, after missing earlier deadlines in 2010 and 2019. In 2024, the country cleared 273 square kilometers - its highest annual total ever. To meet the 2030 goal, it must maintain that pace. Experts say it’s possible if funding stays steady and AI tools are fully adopted. But donor fatigue and new mine-laying threaten that timeline.

What role do rats play in mine clearance?

APOPO trains African giant pouched rats - called HeroRATs - to sniff out TNT in landmines. Weighing less than a kilogram, they can’t trigger explosions. One rat can scan 200 square meters in 20 minutes - a task that takes a human team days. Since 2015, these rats have helped clear over 2,600 anti-personnel mines and thousands of other explosive items in Cambodia, returning land to farmers and communities.

miriam gionfriddo

December 6, 2025 AT 00:58this is the most heartbreaking thing ive ever read and i live in a country where people get shot at concerts bruh i cant even process how a whole nation grows up with death hiding under their feet like a game of russian roulette with dirt

my aunt worked with refugees in the 90s and she said kids would draw pictures of mines like they were toys

how do you even sleep at night knowing your backyard could kill you tomorrow?

Nicole Parker

December 7, 2025 AT 13:09what strikes me most isnt even the numbers or the rats or the ai-it’s the quiet courage of the deminers. people who lost limbs themselves walking back into the same fields where it happened, just so some kid can run barefoot through grass without wondering if today’s the day

theres something sacred in that kind of persistence

we talk about innovation like its tech or money, but real progress is just someone showing up, day after day, with a metal detector and a heart too full to quit

and yeah the funding is a mess and the border thing is terrifying-but what keeps me going is imagining that cassava field in banteay meanchey, blooming because someone refused to look away

Tom Van bergen

December 7, 2025 AT 16:00the real problem is no one wants to admit cambodia is still a war zone and the mines arent just old theyre new and the world is too busy watching ukraine to care

also the rats are cute but they dont solve the root cause which is greed and ignorance

Ben VanDyk

December 8, 2025 AT 13:45the article is well written and the data is solid but i have to wonder-how many of these "hero rats" are just PR stunts to make donors feel good about giving money while the real work gets sidelined

and the ai system sounds impressive until you realize it’s still just guessing based on old patterns

what if the new mines are being laid in places no one has data on

also the 2030 deadline is a joke if funding drops 30%-that’s not a timeline, that’s a death sentence

michael cuevas

December 8, 2025 AT 20:28bruh

the real hero here is the guy who lost his leg and still walks into the field every morning

you dont need a robot to be brave you just need to be broken enough to keep going

Barb Pooley

December 9, 2025 AT 15:31okay but what if the whole landmine thing is a distraction

what if the real goal is to keep cambodia dependent on foreign aid

think about it-why do the same countries keep funding this but never fix their own weapons factories

and who benefits from the fear

the rats are cute but they’re also a distraction from the fact that this is all a controlled narrative

the border mines? probably a setup

the ai? maybe it’s just collecting data on civilians

they always need more money and more attention and never want to let go

its not about clearing land its about control